The history of bird conservation is full of stories regarding the various threats to bird populations as America grew westward after the Civil War. Before then when the country was largely undeveloped it was thought, with bird populations so abundant, that endless harvesting would not impact populations. It took courage to bring awareness when exploitations started happening with the wide-scale hunting of birds in the late 1800’s. This was the beginning of the challenges that would ensue as America’s human population grew and expanded across the nation with settlement. As long as there is human encroachment on their habitat, bird populations will be affected.

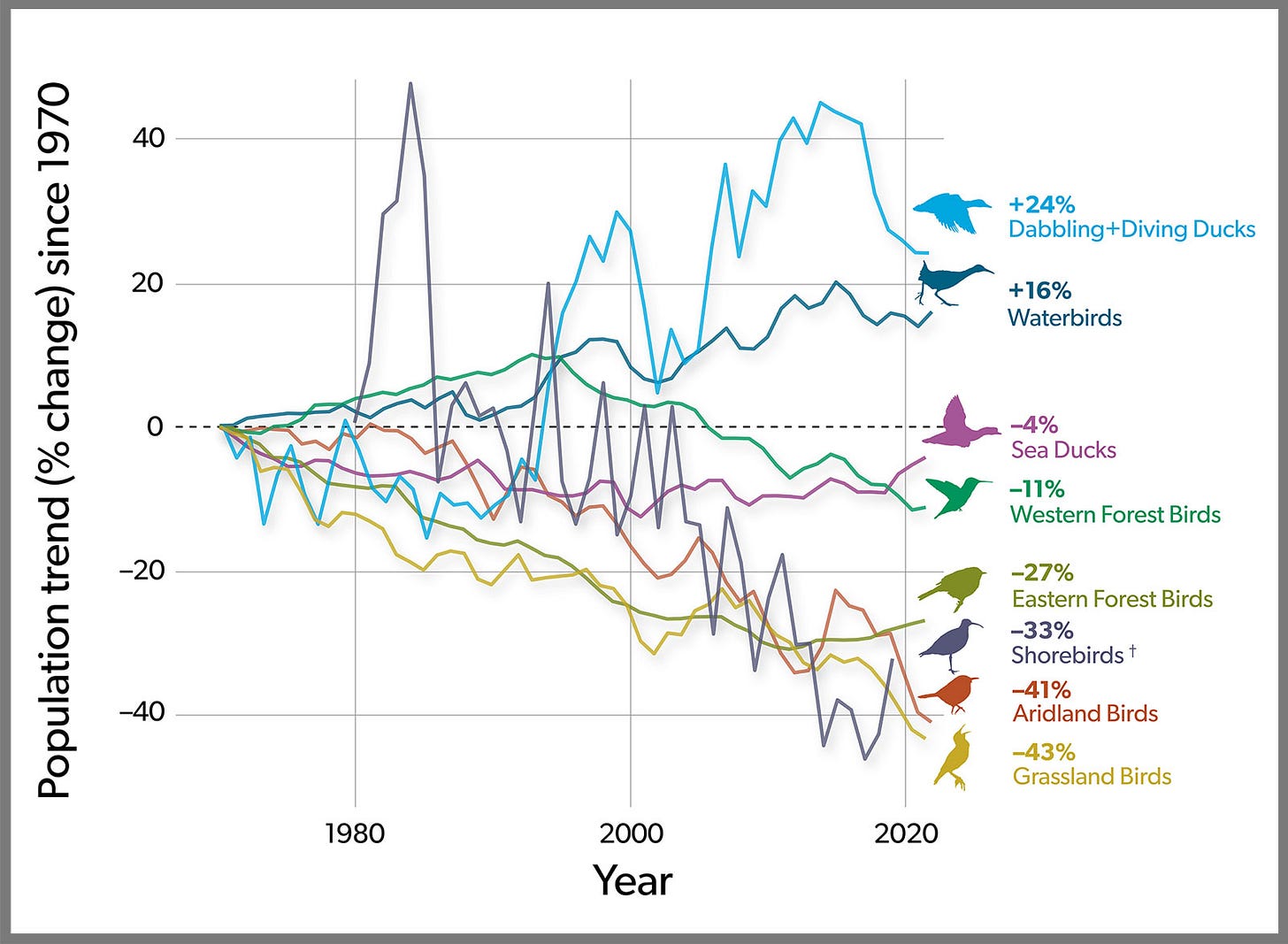

Just out this month is the 2025 report on the State of the Birds which identifies species of concern in America:

A 2019 study published in the journal Science sounded the alarm—showing a net loss of 3 billion birds in North America in the past 50 years. The 2025 State of the Birds report shows those losses are continuing, with declines among several bird trend indicators. Notably duck populations—a bright spot in past State of the Birds reports, with strong increases since 1970—have trended downward in recent years.

About a third of all American bird species are of high or moderate concern due to low populations, declining trends, or other threats. These 229 species should be prioritized in conservation planning to protect existing populations and build toward population recovery.

If it seems easy to be discouraged with this news, it can be hopeful to know that bird populations have suffered big hits in the past with most species recovering. Looking back at the history of some of the population changes birds have endured in last 175 years, due to the settlement and industrialization of America, helps us in looking ahead at the modern day challenges in protecting birds. What is hopeful now is the enormous amount of knowledge, science, education and dedication we have to help identify and counter declines in bird populations before it is too late.

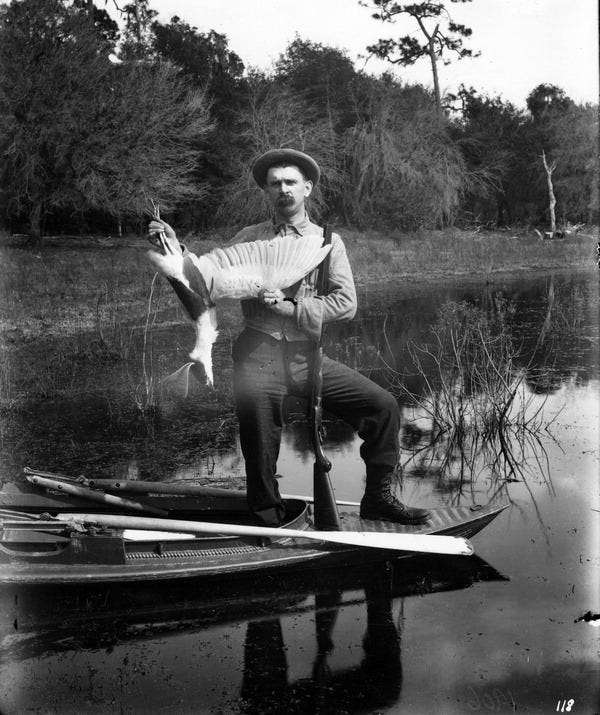

Two examples of past threats to bird populations occurred during a period of mass exploitation in the late 19th century. The first example was due to a frenzied fashion demand for bird feathers to adorn women’s hats. Some of the most prized feathers for these hats were the long plumes called aigrettes that egrets and herons grew during the breeding season. This desire for the showy feathers lead to wholesale slaughter of millions of these beautiful wading birds right on their nests throughout Florida by the so called “plume hunters”.

And it was not only egrets that were targeted. On the East Coast, ten of thousands of terns and gulls were also killed annually. Eventually outrage over the massacres and disappearing birds lead to the formation of the Massachusetts Audubon Society by two Boston socialites in 1896. These two women launched the second oldest conservation group in American history (first being the New York Zoological Society in 1895). This initial Audubon Society’s mission was to spread the word about saving wild birds by not wearing any bird plumage except the feathers of ostriches which did not have to be killed to acquire their feathers. Audubon Societies quickly began forming in other states and successfully lobbied for the passage of the Lacey Act in 1900 that prohibited interstate trade of any illegally taken wildlife. In 1905 these societies were incorporated into the National Audubon Society, with the Great Egret chosen for the organization’s identity and logo. Despite the pushback from the New York millineries trying to protect their high-end hats of fashion, these new conservationists gradually shaped public opinion in favor of giving up a status symbol in order to protect these birds. The shift in awareness then lead to several legislatures enacting bans on the sale of bird feathers in their states. In 1916 this patchwork of legislation became a more cohesive protection when the landmark Migratory Bird Treaty was signed between the US and Canada acknowledging the value of birds, whose annual migrations transcends borders, with a desire for “some uniform system of protection”. In later years amendments to the initial Treaty occurred to include the countries of Mexico, Japan and Russia. This significant piece of conservation law has survived and continues to protect for over 100 years now. And it all began with concerned citizens quickly reacting to stop the destruction in time to allow for the recovery of various species of birds we value sharing in our world today.

History shows us there is hope for restoring bird populations by giving them the protections to adapt or recover from changes that can occur in our shared natural world.

Not all stories ended well. One of the most tragic and shocking story was the demise of America’s Passenger Pigeon. According to the Smithsonian:

The extinction of the passenger pigeon is a poignant example of what happens when the interests of man clash with the interests of nature. It is believed that this species once constituted 25 to 40 per cent of the total bird population of the United States. It is estimated that there were 3 billion to 5 billion passenger pigeons at the time Europeans discovered America.

Early explorers and settlers frequently mentioned passenger pigeons in their writings. Samuel de Champlain in 1605 reported "countless numbers," Gabriel Sagard-Theodat wrote of "infinite multitudes," and Cotton Mather described a flight as being about a mile in width and taking several hours to pass overhead. Yet by the early 1900s no wild passenger pigeons could be found.

Everything about these birds was staggering. For example, an area covering 850 miles in Wisconsin was reported to have 130 million birds nesting together in one summer. Because these birds flew in such large flocks and nested together in colonies, they were an easy shot for the professional hunters that used the railroads to ship them to the city markets back east. The Smithsonian website gives an example:

One of the last large nestings of passenger pigeons occurred at Petoskey, Michigan, in 1878. Here 50,000 birds per day were killed and this rate continued for nearly five months. When the adult birds that survived this massacre attempted second nestings at new sites, they were soon located by the professional hunters and killed before they had a chance to raise any young.

Unfortunately for this species, slaughtering such a large amount of birds at one time, both at their nesting sites and when migrating, never gave them a chance to recover. A bird species dependent on living in such a large flock needs that critical mass to survive so reducing the flock severely causes a tipping point that leads to extinction. If it had survived, the Passenger Pigeon would have struggled as its habitat of large hardwood forests for food and nesting was going to be converted to farmland eventually. Could it have adapted to a smaller range with decreasing forest habitat during the following century? Many speculate that it was only a matter of time before this pigeon species would have met its fate, regardless of the wanton hunting, as the large tracts of the habitat it needed was soon to be plowed under in the nation’s quest for farmland expansion. As it was, this bird species never had the chance to try and adapt given that is was hunted to extinction in just over three decades.

The Passenger Pigeon - North America’s most abundant bird - now lives in our history as a simple reminder that what was once plentiful, can quickly be no more.

Additional notes: Read about historical accounts of the Passenger Pigeon activity in various states throughout the country from Project Passenger Pigeon: https://d2rqvd0kuag1qx.cloudfront.net/Passenger-Pigeons-in-Your-State-Province-or-Territory.pdf

💙💙💙